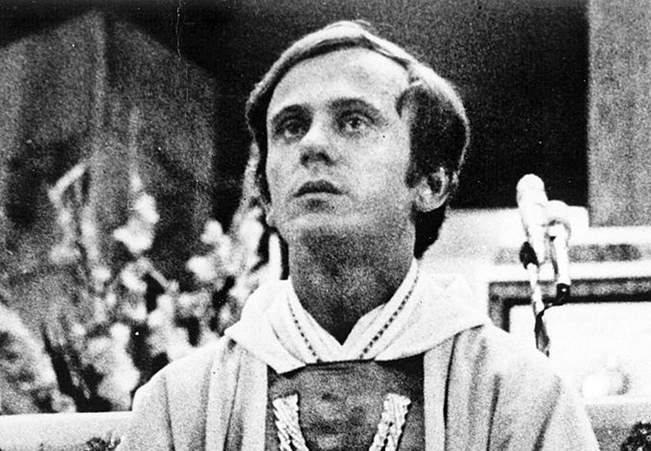

Blessed Father Jerzy Popieluszko was a voice of opposition to the communist regime in Poland. His sermons were full of courage and truth, and at the same time characterised by love for his neighbour and peace. Through his actions he became a symbol of the struggle for freedom, human dignity and the right to profess one’s beliefs. 19 October – the day of the death of Blessed Father Jerzy Popieluszko, who, according to the spirit of the Gospel, preached the principle „overcome evil with good” – was established as the National Day of Remembrance of the Unbroken Clergy.

Father Jerzy’s homilies attracted crowds of the faithful and inspired opposition against totalitarianism. For his steadfast stand, he was kidnapped by SB officers, tortured and then brutally murdered. He died a martyred death for his faith and homeland.

19 October is a day of remembrance, a tribute to all priests and clergy who, through their steadfast and unyielding attitude, remained faithful to God and the Fatherland. They were not defeated or broken. They did not succumb to appearances, they did not compromise with the truth.

We commemorate the spiritual guides who proclaimed the witness of faith, who followed in the truth of Christ, who were often the depositories of the lost statehood. Priests who did not allow the Poles to surrender, building in them a spirit of solidarity and independence. Many of them gave their lives in defence of the Fatherland. Steadfast priests died shoulder to shoulder with their compatriots: in Katyn, Kharkov and Miednoye, but also in concentration camps, persecuted and murdered by the authorities of the People’s Republic of Poland. May their lives and teachings continue to be a source of inspiration for us all, reminding us that in the face of difficulties it is always worthwhile to remain true to one’s convictions.

On this such a special day, but also on every following day, let us remember the Unbroken Clergy who sacrificed their lives on the altar of defending the faith and the Homeland.

Poland’s history, which spans more than 1000 years, shows that Christianity and its values are an inseparable part of our homeland’s tradition. From the dawn of history, Poland’s history has featured figures of indomitable, heroic clergy.

During the Partitions of Poland, when Poland disappeared from the maps of Europe, priests not only engaged in the fight for independence in the spiritual sphere, but also stood up to fight with weapons in their hands. Father Stanislaw Brzóska was one of them.

Priest Stanislaw Brzóska – insurgent priest

A Polish clergyman, general and chief chaplain of the Podlasie voivodship during the January Uprising, war chief of the Łków poviat, organiser and commander of an insurgent detachment made up of peasants.

The chaplain’s unit held out the longest in battle among all in the Kingdom of Poland, and fought until the priest was captured – on 29 April 1865 the Tsarist authorities arrested Father Stanislaw Brzóska, and on 23 May an execution took place in Sokołów Podlaski. The Russians hanged the priest in the presence of a crowd.

The invader wanted to intimidate the local population in this way, but in the meantime made him a martyr for his faith in a free homeland. Fragments of the gallows on which Father Brzóska hung were kept as relics.

The clergy were also involved in Poland’s regaining of independence, the most famous symbol of this period of our history being Father Ignacy Skorupka – chaplain to the soldiers who took part in the Battle of Warsaw.

Priest Ignacy Skorupka

Scout, patriot, social activist who volunteered to be a military chaplain.

During the fighting in the village of Ossów, young Father Ignacy was in the front line of the fighting soldiers. An enemy bullet probably reached him while he was giving the last anointing to a dying soldier. He became a symbol of that dramatic battle.

Władysław Pobóg-Malinowski wrote that Skorupka died „a death more worthy of a priest, as he was stabbed by a stray bullet at the moment when, bent over a seriously wounded soldier, he was giving him his last religious consolations”.

Referring to the times of the Second World War, in those very dramatic times for Poland, priests not only sustained the spirits of the population or provided sacramental ministry, but were themselves murdered both because of their nationality and because of their hatred of the Church, which was treated by the German and Soviet occupiers as an enemy.

A heroic and hallowed example of a clergyman of those times is Saint Maximilian Kolbe.

Father Maximilian Kolbe – holy martyr

„Follow Christ – love and serve”. St Maximilian Kolbe.

Missionary, Franciscan, founder of the Niepokalanów monastery – a centre for religious life and the apostolate of the press. He published the magazine „Knight of the Immaculate”.

During his stay in Japan, Father Maximilian Kolbe managed to build a friary-city called the Garden of the Immaculate (Mugenzai no Sono), where he organised a new Franciscan community.

When the war broke out, most of the inhabitants of the monastery were forced to leave Niepokalanów as a result of the persecution, and refugees, rebels, the wounded and the unemployed – including those of Jewish origin – took refuge within its walls. Father Maximilian’s attitude did not suit the authorities of the time; he was arrested many times and interrogated at the Pawiak prison. On 28 May 1941, Father Maximilian Kolbe was sent to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp. He was given the number 16670.

In July 1941, after an escape by one of the prisoners, the camp commandant sentenced ten people to death by starvation. Although Father Maximilian Kolbe was not in this group, he voluntarily exchanged himself with the victim.

He justified his decision as follows „I am nearly fifty years old, I have lived my life, and this one has a life ahead of him. He has a wife and children”. Thanks to his steadfast attitude, he saved the life of Franciszek Gajowniczek in exchange for sacrificing his own. Franciszek Gajowniczek died on 14 August 1941, killed by a phenol injection as the last of the prisoners locked in the starvation bunker in the basement of block 11, the so-called „death block”.

From the outset, the communist authorities in post-war Poland regarded the Church as a group threatening the state, which needed to be controlled and eliminated from the country’s public life. The clergy who opposed the communist system sought to subjugate the new authorities by means of terror, and when they encountered resistance, to annihilate them.

Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński – Primate of the millennium

He was ordained a priest in 1924. After the outbreak of World War II, he hid from the Gestapo. During the Warsaw Uprising, he served as chaplain of the Kampinos group of the Home Army, operating in Laski, and – under the pseudonym Radwan III – as chaplain of the insurgent hospital.

In March 1946, he was nominated Bishop of Lublin, and in November 1948, Pius XII appointed him Archbishop of Gniezno and of Warsaw – the Primate of Poland. In January 1953, the Pope included him in the College of Cardinals.

During the period of communist repressions against the Church and society, he defended the nation’s Christian identity. At the same time, he was the initiator of a political settlement with the state authorities. Despite the compromise between the Church and the authorities, the government decided to interfere openly in the internal life of the Church, wanting to decide on the principles for filling Church positions. Faced with these events, the Primate uttered his famous 'non possumus’ (we cannot).

He was imprisoned. By 1956, he was interned in Rywałd, Stoczek, Prudnik and Komańcza.

„If I am in prison and they tell you that the Primate has betrayed the cause of God – do not believe. If they say that the Primate has unclean hands – do not believe. If they say that the Primate chickened out – do not believe it. If they say that Primate is acting against the Nation and his own Homeland – do not believe it. I love my Homeland more than my own heart and everything I do for the Church, I do for her”. – these were the Cardinal’s words on 25 November 1953.

He consistently and decisively opposed the Marxist conception of social life and defended human dignity and rights. The Primate of the millennium was both a moral and spiritual authority, but also a co-creator of the changes that led to the fall of communism. In 1980-81, he supported and protected the nascent 'Solidarity’ movement from danger.

Cardinal Wyszynski was instrumental in the election of Karol Wojtyla as Pope.

Cardinal Wyszynski died on 28 May 1981 in Warsaw. The funeral ceremonies gathered crowds of the faithful and clergy. Representatives of the Holy See and the authorities of the People’s Republic of Poland attended.