Poland’s regaining of independence was a long and complicated process. This possibility arose primarily through the outbreak of the First World War, during which the previous allies, i.e. the countries that had partitioned the Republic, at the end of the 18th century, fought against each other.

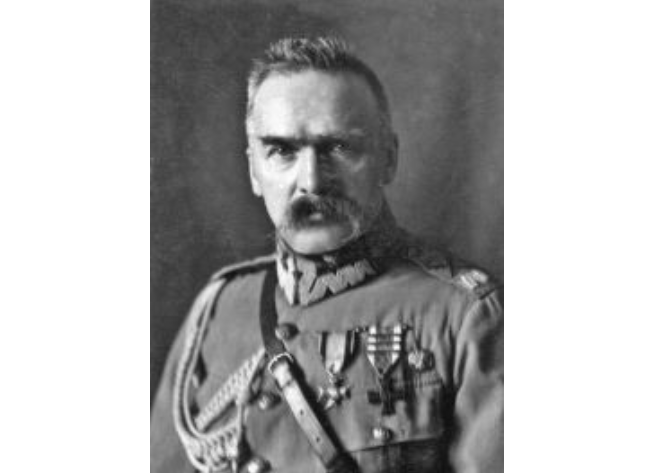

From the Polish point of view, it was important that both Austria-Hungary and Germany, i.e. the Central Powers, and the Russians tried to pull the Poles to their side. Ultimately, Austria-Hungary and Germany came closest to a compromise with the Polish representatives. The leaders of these countries, as early as November 1916, announced the so-called „Act of 5 November”. This document announced the creation of the Kingdom of Poland, which was to remain in 'communion with both Allied Powers’. Subsequently, in January 1917, the Provisional Council of State of the Kingdom of Poland was established to prepare the state institutions that were to function in the Kingdom of Poland. Ultimately, the Council failed to fulfil the tasks it had been entrusted with, as it dissolved itself at the end of August 1917, following the so-called oath crisis, during which soldiers of the First and Third Brigades of the Polish Legions, loyal to Brigadier Jozef Piłsudski, refused to swear allegiance to the Austro-Hungarian and German emperors.

In view of the above, the leaders of the two powers decided to appoint a successor to the Provisional Council of State. On 12 September 1917, this became the so-called Regency Council. This body was to act as a kind of head of state until a regent took over power in the Kingdom of Poland. Three important and universally respected figures were appointed to the Council, i.e. Aleksander Kakowski, Archbishop of Warsaw, Prince Zdzisław Lubomirski, President of Warsaw, and Count Józef Ostrowski, Honorary President of the Party of Real Politics.

Despite the fact that the Council had rather limited competences, mainly concerning the judiciary, education or certain administrative issues, it played an important, but also controversial role in the process of Poland regaining its independence. Of course, during the period in question, the Council was not the only organisation trying to fight, more or less successfully, for Polish interests. Earlier than the body just mentioned, the Polish National Committee was established in Paris, headed by Roman Dmowski. Moreover, from almost the very beginning of the First World War, Polish units fought on both sides of the conflict. The achievements of the soldiers commanded by Jozef Piłsudski or Józef Dowbor-Muśnicki, among others, went down in gold. In addition to the above-mentioned, the eminent composer Ignacy Jan Paderewski lobbied for Poland, while in the parliaments of the partitioning states Wincenty Witos, Wojciech Korfanty and others did so. In short, Poland had many ambassadors striving to restore its place on the map of Europe and the world. Nevertheless, they all encountered difficulties of various kinds.

Such problems also affected the Regency Council, which, for example, from the very beginning of its existence had to agree all its decisions with the partitioning authorities. Problems of this kind meant that the Council never really gained respect in the eyes of Polish society. Above all, Poles did not like the source of the body’s appointment, i.e. the two partitioning states. Secondly, our compatriots felt that the Council was too submissive towards its principals. Professor Andrzej Chojnowski, an eminent expert on that era, stated: „They [the Council members] were appointed by both emperors. They represented a conservative spirit, a conservative attitude, a group of people who were materially established”.

Despite these criticisms, the Council had its achievements. Among other things, it succeeded in establishing a government of the Kingdom of Poland, with Jan Kucharzewski as its 'President’ [i.e. Prime Minister]. In addition, the Council lodged a protest against the Treaty of Brest, signed in February 1918, between the Central Powers and the recently proclaimed Ukrainian People’s Republic, in the point concerning the surrender of Ukraine, Chełmszczyzna and part of Podlasie. However, the Council took its most important decisions in the autumn of 1918, when the defeat of the Central Powers in the First World War was really imminent. On 7 October 1918, it promulgated a significant document whose title read: „Declaration of Independence of the Kingdom of Poland”, which among other things stated: „Let all that can divide us mutually be silent and let one great voice sound: A united independent Poland”.

The next important step was the assumption of authority over the so-called Polonische Wehrmacht, or Armed Forces of the Polish Kingdom. Although this was a small force, numbering only a dozen or so thousand soldiers, it became the nucleus of the Polish Army, which in the following days began to be gradually formed under the command of General Tadeusz Rozwadowski.

In addition to the above, the Regency Council set up another government under Józef Świeżyński, and tried to bring out of internment a man who was already regarded as a living legend, i.e. Jozef Piłsudski. Piłsudski, as the former commander of the First Brigade of the Legions, was locked up in a Magdeburg fortress after the Oath Crisis. At that time, his social prestige was steadily growing, inversely to the popularity of the Regency Council, against which even Świeżyński rebelled.

The Prime Minister was eventually dismissed on 4 November 1918. By this time, the fate of the Council was also sealed. Kakowski, Lubomirski and Ostrowski began to realise this as they followed the military and political events on the European scene. First and foremost, all three partitioning countries lost, or withdrew from the war effort, as they ran into huge internal problems that could result in the destruction of their statehood. In view of the above, Germany, struggling with the 'Red’ revolution, decided to release Piłsudski from Magdeburg and send him to Warsaw.

In the Polish capital, the Brigadier appeared as early as 10 November 1918 and faced political fragmentation. For example, the Kingdom of Poland was ruled by the Regency Council. Nevertheless, in Lublin, the so-called Provisional People’s Government of the Polish Republic was formed with Ignacy Daszyński at its head, in Kraków, the Polish Liquidation Commission for Galicia and Cieszyn Silesia was established, headed by Wincenty Witos, and in Poznań, the Supreme People’s Council, which included Wojciech Korfanty.

11 November 1918 saw the start of the actual process of rebuilding Polish statehood. In its first move, the Regency Council placed power over the army in Piłsudski’s hands, and a day later entrusted him with the mission of forming a government. At the same time, on 14th November, the Council decided to dissolve itself, handing over all its competences to the Brigadier.

Meanwhile, events began to gather momentum. On 16 November 1918. Piłsudski announced to the world the creation of the Polish state, and two days later appointed the first Prime Minister of the Second Republic – Jędrzej Moraczewski. The next step taken by Piłsudski was to appoint himself the so-called Provisional Chief of State. This took place on 22 November 1918. From then on, the Polish state had not only a leader, but also a leader who, in the months to follow, had to demonstrate his diplomatic, political and military skills. For a very dangerous time was coming for the nascent Polish statehood.