In November 1918. The Republic of Poland regained its independence. This was possible thanks to, among other things, the resolution of the First World War. In the course of this bloody conflict, the states that had deprived Poland of its freedom and sovereignty over a century earlier fought against each other, losing influence in Central Europe. However, this was only one element leading Poland to freedom. Another, no less important than the one mentioned above, was the activity of Polish statesmen, including Roman Dmowski, Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Jozef Piłsudski and several others. Thanks to their activity, Poland came into being in November 1918.

It was then that Piłsudski returned to Warsaw. Although he was one of several so-called fathers of independence, he played a decisive role in the period under discussion. Above all, it was to him – a soldier and prisoner of war, both Russian and German, shrouded in legend – that the Regency Council – the supreme authority of the Kingdom of Poland – handed over power. First it gave him supremacy over the army, and then over the whole of the then-forming state. Piłsudski thus gained the right to represent his Homeland on the international arena.

As a man of action, he knew that it was necessary to act prudently, but also without unnecessary delay. It was largely thanks to him that the first government of a free Poland was formed, headed by Jędrzej Moraczewski.

At the same time, Piłsudski decided on an unprecedented move. He decided to announce to the world that Poland had come into being, as a free and independent country. Interestingly, the independence of the Republic had already been declared on 7 October 1918. Regency Council, publishing the 'Declaration of Independence of the Kingdom of Poland’. This document was extremely important, as it made it possible to create the structures of the Polish Army, which was then commanded by General Tadeusz Rozwadowski. Nevertheless, the act just mentioned did not reach the cabinets of the mighty of this world, including the leaders of France, the United States or Great Britain.

In view of the above, Piłsudski, together with Tytus Filipowicz – head of the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, who held his post for two days: 16-17 November 1918, and was later deputy head of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, signed another document – a dispatch notifying the creation of the Polish state, which was sent out to the world on 16 November 1918. Its recipients were the President of the United States, the leaders of Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, the Emperor of Japan and „the Governments of all the belligerent and neutral States”. The contents, however, read as follows:

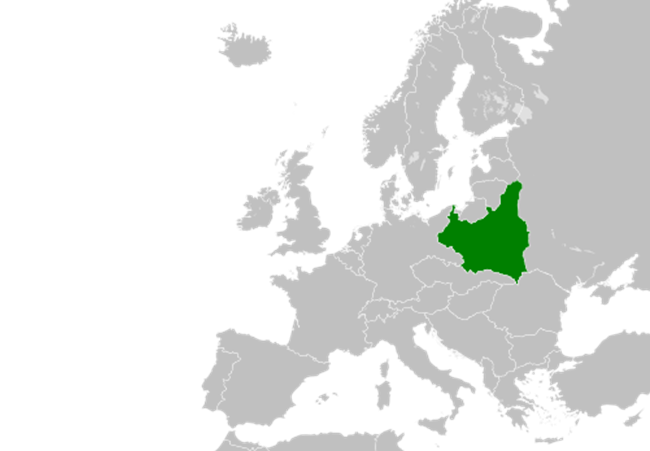

„As Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Army, I wish to notify the governments and nations of the belligerent and neutral states of the existence of an Independent Polish State, encompassing all the lands of a united Poland.

The political situation in Poland and the yoke of occupation have so far prevented the Polish nation from speaking freely about its fate. Thanks to the changes brought about by the great victories of the allied armies, the restoration of Poland’s independence and sovereignty is now an accomplished fact.

The Polish State is being established by the will of the whole nation, and is based on democratic foundations. The Polish Government will replace the reign of violence that had weighed down Poland’s fate for one hundred and forty years with a system built on order and justice.

Relying on the Polish Army under my command, I hope that henceforth no foreign army will enter Poland before we have formally expressed our will in this matter. I am convinced that the mighty democracies of the West will lend their aid and fraternal support to the Polish Republic, reborn and independent”.

In addition to the above note, Filipowicz, on 17 November 1918, sent out another very important dispatch. It was addressed to the Foreign Ministers of Great Britain, France, Portugal, Italy, the United States and Japan and contained a proposal for an exchange of diplomatic representatives.

In a word, the aforementioned acts were the first to declare the creation of a Polish state. Significantly, however, the leaders of the world’s most important societies recognised Poland’s independence. First, on 20 November 1918, the Germans did so! Only after them did other Western countries accept the return of the Republic to the map of Europe. Thus, representatives of Poland were able to participate in the Paris Peace Conference held in 1919-1920, although Poland had to defend its independence several times over the following months.

It was a bit of a giggle of history that both of the dispatches described above were sent through the 'WAR’ radio station, located between the Third and Fourth Bastions of the Warsaw Citadel. The radio station itself had been taken over from the Germans and was still in the service of the Polish army for several years. More important, however, was the place where this radio station was located, the Citadel in Warsaw. This place was a symbol of tsarist terror against the Polish population. It was built after the end of the November Uprising, on the orders of Tsar Nicholas I. The fortress was a control and pacification point against the Polish population active in the independence underground. At the same time it served as an investigative prison, where investigations were carried out against many activists of the Polish nineteenth-century underground (imprisoned there were, among others, Roman Dmowski, Jozef Piłsudski and Father Piotr Ściegienny), and was also a place of execution for persons of merit in the struggle for freedom and independence of the Polish state. In the Warsaw citadel, the Russians murdered, for example, Stefan Okrzeja and Romuald Traugutt.

In summary, the site of Russian crimes against the Polish people was instrumental in announcing to the world that Poland had come into being as a free, sovereign and independent state.